We arrive in the Old Town of Prague after an uneventful train trip followed by a harrowing taxi ride. The driver drops us off short of the hotel entrance, is angry with me for leaving my car door open when I get out, and charges what we later realize is a cartel-type price. We settle into a luxury suite, replete with thick black curtains and scarlet brocade bedspread, that the hotel has given us for no discernible reason except that we will be here for five nights.

We walk out the front door (or is it the back entrance?) and find ourselves in the midst of a babel of foreign tongues. I can discern German occasionally, but the rest? Czech? Russian? Ukrainian? Slovak? Bosnian? Herzogovinian? Hungarian? Do I know? Absolutely not.

Lots of tourists wandering about in the heat and humidity. Large family groups, often Asian or Indian. Young Chinese couples. Old English couples. Groups of European girls with matching t-shirts. Groups of young men who whistle in harmonic unison as they walk down the street, and sometimes include a made-up decked-out transvestite in their midst. The number of Spanish-speaking families surprises me, but then again they are among the few I can understand.

For the first three days we get lost every time we emerge into the jumble of packed narrow alleys that go off in all directions, angles and curves. Neither Walter’s sense of direction nor my assiduity with maps makes a difference. We get lost on the way to the main square with the famous clock, on the way to the Charles River, on the way to the Jewish Quarter, and even on the way to look for a place to have dinner.

The famous astronomical clock in a main square has the twelve apostles in a procession to admonish against 1) Vanity—a figure who admires himself in a mirror. 2) Usurious greed—a miser (Jewish?) holding a bag of gold. 3) Lustful earthly pleasures—a turbaned figure on the prowl. And 4) all are haunted by death—a skeleton that strikes the time upon the hour.

The streets are crowded, and the cobblestones that look so picturesque are souneven that it’s not always comfortable to walk. But walk is what we do—the trams and buses seem formidable, given the language, and unlike France and Switzerland, everyone here does NOT speak English.

Our first dinner is in a basement with steep stairs that take us way below street level. We are starved because there was no food on the train, so it’s early. The only other customers are a large Chinese tour group, posing for pictures with the Czech musicians who came to entertain them. We order what the waiter recommends as a Czech specialty, and the platter for two has more meat—pork, beef, lamb, veal, duck—than I have ever seen before in one dish. I attack the duck, and get full before I can finish it, let alone make a dent in anything else. We take lots of leftovers back to our hotel room’s mini-fridge. The next day I pull out some more duck, and after that I can’t even look at it again.

The first full day we do the obvious, and walk cross the Charles Bridge. Prague’s beauty emerges in all the views of slanted red-tiled roofs among green trees.

Medieval religious figures loom from the air, staring down from the sides of bridges, the tops of spires, the niches in various buildings.

All this wears us out, and we sleep much of the afternoon.

The second day we take a long walking tour. Our guide has good English, but her Czech cadence requires concentration, and I can lose track. Our time includes a too-short boat ride with a cool breeze, on the Vltava River from one end to the other of the part allowed for tourist cruises; a group lunch at a decent restaurant; tram rides up and down the hill, and time in the Prague Castle, which is the largest ancient palace in the world and the current home of the President of the Czech Republic.

Stories abound of people thrown to their death off the Charles Bridge as punishment for the wrong beliefs. (I assume the fights were over Christian tenets, although how is it that I have a photo of a crucifixion draped in Hebrew letters?) There is a whole Museum of Medieval Torture, which we decide to skip.

The third day we do the Precious Heritage Tour through the Jewish Quarter. So the Prague shtetl, once walled with the residents forbidden to leave, functioned for 800 years, longer than any other such community in Europe. The graveyard got crowded, with bodies buried six deep, until 1781, when Josefov of the Roman Empire signed a document magnanimously titled the Toleration Edict, and once Jews could roam throughout the land, they began to bury their dead elsewhere.

(Eventually the whole area got named Josefov, even though the same guy had the nerve to turn down Mozart as his court musician because he used too many notes in his compositions.)

Anyhow, Jews had to wear distinctive garb, and I guess they did it with pride because in places the required hats, whether round or long, are integrated into the old religious art. But during World War II, of course, the Nazis arrived and occupied the entire city.

Yet they left the old sections largely untouched. Why? Because Hitler liked Prague, and considered it all his. That’s why.

Next came that mandatory ugly six-pointed yellow cloth star, and after that, deportation. First to Terezín, Hitler’s “model” concentration camp with its instructive slogan over the entering arch that “Work Makes One Free.” Later to Auschwitz and Treblinka, as the Final Solution unrolled. Even with all this, though, the Quarter remained quite intact.

Why? Because Hitler intended to use it to establish a museum to an “extinct race.” That’s why.

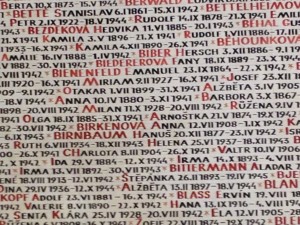

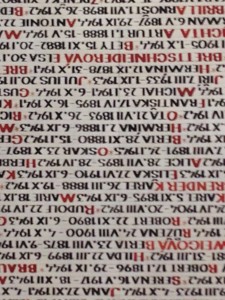

And indeed, though the “race” has not been extinguished, the Jewish museum has walls devoted just to the names of those who perished.

So now? The neighborhood blends in with surrounding environs. You can tell Jewish people are around somewhere, because there is a functioning synagogue and at least one new apartment building has balcony mosaics laced with gold, that include one with a six-pointed star in close proximity to a disconcerting pile of money.

And there is a spectacular modern statue of Franz Kafka.

The fourth day we get on a Communism Tour led by a young cynic who had never even visited the Museum of Communism, which we returned to later and which, after all, should be a requirement for the job, no?

Our guide takes us by tram to an underground bunker, built to house civilians in the event of nuclear war. Piles of gas masks, and storefront window displays of whole families wearing them. Slogans, supplies, requisitions, displays everywhere, all grim.

A small bank of theater seats, sprang up inside this underground labyrinth after the fall of communism in ’89. On the stage is a machine gun on a mound of earth, pointed at the absent audience.

Prague today, though,is no longer grim—at least in its tourist sections—largely because it is permeated with good free live music. On the Charles Bridge there are small groups that play and sing classical pieces like the pros that they are, along with the occasional scruffier group tossing out rock and roll that sounds sorta like folk music. After the Jewish tour we turn a corner to find a group, again with classical instruments (at least one cello seems mandatory) singing rowdy Czech (?) songs.

The pianist at our hotel bar, a gray-haired guy at least our age, can and does play everything. Mozart, Joplin, Chopin, Beatles, Haydn, Carly Simon, Schubert, James Taylor and more, for hours without a sheet of notes in front of him, whether anyone is in his space to listen or not. The tendrils of his music curl up and encircle our third floor balcony all of our evenings there.

On the final afternoon as we start home from the far side of the Charles Bridge, we stop at a place where we can see down onto a flat busy plaza, and out of the bustle materializes an entire symphony orchestra, gathered and ready. The crowd standing around in a semi-circle turns out to be a chorus. The conductor paces about, stands on a stool, takes the time to face everyone in turn, lifts his arm and they play.

We stumble on a nice place for dinner on that same last night. Upstairs to the third floor, soft seats, white tablecloths, more silverware at each setting than you can possibly use. Johnny Walker Black Label scotch and soda for me, red wine for Walter. Succulent meats, potatoes cooked in a way that is mysterious and unfamiliar, and excellent apple strudel. And the story behind the setting, as told by a waiter old enough to have experienced it first-hand?

This very edifice managed to survive an American bombing on a cloudy day during WWII when the commander mistook Prague for Dresden. A dud bomb crashed through the roof all the way down to the ground floor with no explosion. It had to be detonated later, I guess. In any event, here was the building, the restaurant, staff from the era before the fall of communism, music tinkling merrily from keyboards on each floor—all still present as a current chapter in the many tales of Prague.